Biological metal–organic frameworks for natural gas purification and MTO product separation

Abstract

The use of porous solid adsorbents is an effective and excellent approach for the separation and purification of methanol-to-olefins product and methane (CH4). In this particular study, a series of adenine (AD)-based biological metal–organic frameworks (Bio-MOFs) {Their general formula is Cu2(AD)2(X)2 [X = formic acid, acetic acid (AA), and propionic acid]} were proposed, which exhibited remarkable efficiency in the purification of CH4 and the separation of C3H6 from methanol-to-olefins product, ultimately yielding purified C2H4. The experimental findings demonstrate that different terminal ligands induce alterations in the pore microenvironment, consequently leading to variations in adsorption capacities and stability. Specifically, Cu-AD-AA exhibits the highest adsorption capacity and selectivity among the three MOFs, as confirmed by static adsorption isotherm testing and theoretical evaluation using ideal adsorbed solution theory (IAST) simulation. At 298 K and 1 bar, Cu-AD-AA exhibits 786 and 10.9 selectivity for C3H8/CH4 and C3H6/C2H4, respectively, surpassing the majority of MOFs materials. Furthermore, breakthrough experiments conducted in ambient conditions reveal that Cu-AD-AA possesses commendable separation capabilities, enabling one-step purification of C2H4 at varying proportions (C2H4/C3H6 = 50:50, 50:20, and 90:10), along with satisfactory recycling performance. Importantly, the synthesis of Cu-AD-AA utilizes simple and easily obtainable raw materials, thereby offering advantages such as cost-effectiveness, low toxicity, and facile synthesis that enhance its potential for industrial applications.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, light hydrocarbons as important chemical raw materials and fuels have gained significant application in various fields[1,2]. Natural gas is widely recognized as a clean energy that can be extensively applied in power generation, domestic fuel, and even in the automotive industry[3-5]. Pyrolysis gas, which is a major source of natural gas, primarily consists of methane (CH4) and light hydrocarbons (C2-C3) such as acetylene (C2H2), ethylene (C2H4), ethane (C2H6), and propane (C3H8)[6,7]. However, the presence of these light hydrocarbon impurities not only decreases the conversion rate of CH4 but also affects the stability of cyclic processes during storage and the safe transportation through pipelines. Therefore, it is necessary to remove these impurities to ensure the purity of the natural gas before it can be liquefied and transported[8]. Interestingly, these C2 and C3 light hydrocarbons also serve as essential raw materials in the petrochemical industry. Effective separation of these light hydrocarbons from pyrolysis gas not only enhances the purity of CH4 but also enables efficient utilization of C2-C3 molecules.

In addition to CH4 purification, the industrialization of the methanol-to-olefins (MTO) reaction has witnessed significant advancements in recent years[9,10]. MTO reaction is a significant and advanced method for producing C2H4 from coal and natural gas, with the product consisting of approximately 21 wt% C3H6 and 51 wt% C2H4[11,12]. Therefore, the separation of C3H6 and C2H4 in MTO product is crucial for downstream applications[13,14]. However, the separation of C3H6 and C2H4 poses a complex and challenging task due to their relatively low boiling points (225.4 K for C3H6 and 169.4 K for C2H4) and similar kinetic diameters (4.6 Å for C3H6 and 4.2 Å for C2H4)[15-17]. Due to the relatively low boiling point of these light hydrocarbons, conventional methods for separating light hydrocarbons often rely on high pressure and low temperature distillation processes. Nevertheless, this approach suffers from several drawbacks including high energy consumption, large footprint, and complex operation[18]. To address these issues, combining physical adsorbents with pressure swing adsorption (PSA) technology has emerged as a promising alternative[19]. This method, based on the principle of physical adsorption, can be conducted at ambient temperature and pressure, not only offering a simple operational procedure but also ensuring low energy consumption. Among various physical adsorbents, metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) materials have gained significant attention in materials science due to their excellent properties[20-22].

MOFs are crystalline structures formed through coordination bonds between metal ions or clusters and organic ligands[23-25], which exhibit higher specific surface area, porosity, and adjustable structure compared to traditional materials such as porous silicon, activated carbon, and zeolite[26-28]. As a result, it offers a broader range of potential applications; for example, it has fantastic uses in the fields of gas adsorption and separation, energy conversion, drug delivery, water vapor capture, catalysis, and sensing[29-33]. In industrial settings, MOFs materials can be designed to purify natural gas and separate MTO product based on slight physical differences between these light hydrocarbons[34]. For example, C3H8 and C2H6 molecules have slightly larger sizes and polarizabilities than CH4. By designing pore size close to C3H8 and C2H6 molecules and enhancing interaction between the framework and gas molecules, efficient natural gas purification can be achieved[35]. Similarly, for C3H6 and C2H4, pores can be designed based on their difference in polarizability, and the introduction of specific organic functional groups can increase the van der Waals interaction between the host material and guest molecules, thereby facilitating the efficient separation of

Thanks to the progress of reticular chemistry, MOFs materials have enabled precise regulation of pore environments to selectively adsorb specific gas molecules[38]. Generally, two strategies are employed for regulating pores in MOFs. One involves substituting metal ions to achieve sub-angstrom precision regulation[39], while the other adjusts ligands to accurately regulate the structure by altering the length and introducing functional groups[40,41]. However, the first approach is limited by different coordination modes of metal ions and restricted choices of metals, making it difficult for widespread use. In contrast, the second technique, which utilizes organic ligands, is more commonly adopted due to the wide range of options available. In the pursuit of industrial-grade production, factors such as environmental friendliness and cost-effectiveness must be considered. Traditional MOFs heavily rely on ligands produced through organic synthesis[42]. Many of these ligands, particularly those with special functional groups (such as -NH2, -CH3,

Based on the aforementioned considerations, we have developed a solvothermal synthesis method for three Bio-MOFs with the traditional lvt topology. The rigid ligand adenine (AD), abundant in nitrogen atoms and amino groups, is an excellent choice for constructing stable MOFs with active sites. While Cu-AD-AA and Cu-AD-PA structures were previously reported using diffusion methods, in this study, we successfully synthesized them through solvothermal techniques[49], which are simpler and more scalable for large-scale production, resulting in defect-free crystals suitable for gas separation applications. Cu-AD-FA was reported for the first time, and its structure was analyzed by single-crystal X-ray diffraction experiments. Structural analysis reveals that different terminal carboxylic acid ligands significantly influence the pore environment (channel size, pore volume, active site) of materials. It is noteworthy that previous researchers have conducted some gas adsorption and separation studies for Cu-AD-AA and Cu-AD-PA materials. For example, in 2012, Pérez-Yáñez et al. explored the CO2/H2 and CO/H2 separation properties of these two materials[50]. Similarly, in 2020, Li et al. investigated the separation performance of Cu-AD-PA specifically for C2H2/CO2[51]. However, a comprehensive investigation into the separation ability of light hydrocarbons, especially for C2H4/C3H6 separation, has not been done so far. Therefore, the light hydrocarbon adsorption separation of these materials was systematically studied in this work. Among them, Cu-AD-AA has exhibited excellent adsorption and separation capacity, demonstrating great potential in natural gas purification and MTO product separation.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials and methods

The chemicals used in this investigation were acquired from commercial sources and were not subjected to further purification. Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images were captured using a JEOL JSM-7800F microscope. Dynamic light scattering measurements were conducted at 25 oC on a Malvern Zetasizer Nano-ZS90 instrument (detection range: 3-3,000 nm). Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) data were collected using a Rigaku D/max-2550 diffractometer with Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å). Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) data were obtained using a TGA Q500 thermogravimetric analyzer under air conditions at a heating rate of 10 oC min-1. Surface area was measured using N2 adsorption isotherms at 77 K with a Micromeritics ASAP 2420 instrument. CH4, C2H2, C2H4, C2H6, C3H6 and C3H8 adsorption isotherms were determined using a Micromeritics ASAP 2020 instrument. The breakthrough experiments were conducted in a homemade HPMC41 gas separation test system (Nanjing Hope Analytical Equipment Co., Ltd).

Synthesis of Cu-AD-FA

A mixture of Cu(NO3)2·3H2O (12 mg, 0.05 mmol), AD (16 mg, 0.12 mmol), N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF, 2.0 mL) and FA (0.3 mL) was sealed in a 20 mL vial and heated at 65 oC for 24 h. The green octahedron crystals were gathered and washed with EtOH and then dried in air [20 mg, yield 64%, based on Cu(NO3)2·3H2].

Synthesis of Cu-AD-AA

A mixture of Cu(NO3)2·3H2O (2.4 g, 0.010 mol), AD (3.2 g, 0.024 mol), N,N-dimethylacetamide (DMA,

Synthesis of Cu-AD-PA

A mixture of Cu(NO3)2·3H2O (2.4 g, 0.010 mol), AD (3.2 g, 0.024 mol), N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP,

X-ray crystallography

Crystallography data of Cu-AD-FA was collected at room temperature on a Bruker Apex III CCD single crystal diffractometer by graphite-monochromated Mo-Kα (λ = 0.71073 Å). The structure was solved by a direct method and then refined by a least square method on F2 in Olex2. The hydrogen atoms were added geometrically. The formula of Cu-AD-FA is Cu2(AD)2(FA)2(DMF)1.5. The CCDC number of Cu-AD-FA is 2312625. Crystal data and structural refinement results are summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Crystal structure description

By adjusting the size of the terminal ligands in the channel in a unified structure, the channel environment can be effectively improved to achieve a small regulation and a large influence[52,53]. For example, the aqueous synthesis of MOF-808, previously reported by our group, improved the water adsorption performance by modifying the carboxylic acid-based modulator, enabling the straightforward tuning of the pore environment[54]. In this study, a classic Bio-MOF platform is utilized, which was composed of AD ligand, Cu2+ ions and terminal ligand (FA, AA, PA). It is worth mentioning that similar structures were observed in Bio-MOF-11-14 series, which consisted of cobalt ions with AD and terminal carboxylic acid ligands. Specifically, Bio-MOF-11 was isoreticular to Cu-AD-AA, and Bio-MOF-12 was isoreticular to

The structure of Cu-AD-FA was determined by single-crystal X-ray structure analysis, and the other two structures were proved by PXRD characterization [Supplementary Figure 3]. The structure of these three Bio-MOFs is illustrated in detail in Figure 1. In Figure 1A, Copper dimer clusters are connected to AD ligands, forming a three-dimensional structure. Each copper dimer is linked by four AD ligands and two monocarboxylic acids. Each AD ligand links to two copper dimers, resulting in one nitrogen atom and one amino group per AD within the structure, which can serve as polar adsorption sites. These MOFs exhibit the same lvt topology as the aforementioned MOFs [Supplementary Figure 4A]. However, different terminal ligands cause slight changes within the pore [Figure 1B-D]. The steric hindrance of the terminal ligands gradually transforms the pore size from narrow to more open. To observe this change more directly, Supplementary Figure 4B-D show that the distance between nitrogen atoms and amino groups at the same position increases as the size of the terminal ligands enlarges (3.2 Å for Cu-AD-FA, 4.4 Å for Cu-AD-AA and 5.4 Å for Cu-AD-PA). Instead of conforming to a traditional one-dimensional channel, the structure of this series exhibits three-dimensional intercrossed channels [Figure 1E-G]. Notable alterations occur within the interior environment of the cavity due to variations of the terminal ligands. The inner wall of the channel is non-uniformly smooth; thus, measurements primarily focus on the length of crossed positions and long cavity length. In the Cu-AD-FA structure depicted in Figure 1H, there are two dimensions of cavities within the Z-shaped channel: a longer cavity measuring approximately 11.2 Å in length and a narrower cavity with a width of 8.2 Å. Unlike Cu-AD-FA, Cu-AD-AA incorporates methyl group into its skeleton, which widens the pore size. Consequently, both the long cage and narrower cavity increase to approximately 12.7 Å and 8.8 Å, respectively [Figure 1I]. Notably, more pronounced changes occur with Cu-AD-PA, where ethyl group is introduced into the Cu-AD-FA structure. While the long cavity size remains around 12.7 Å, the narrow cavity reduces to about 6.8 Å [Figure 1J]. This slight change in the tunnel environment is highly intriguing, prompting us to investigate their adsorption properties concerning light hydrocarbons.

Figure 1. Structure of Cu-AD-FA, Cu-AD-AA and Cu-AD-PA. (A) The composition structure of metal clusters; Ball and stick diagram of (B) Cu-AD-FA; (C) Cu-AD-AA; and (D) Cu-AD-PA. The three-dimensional intercrossed channels of (E) Cu-AD-FA; (F) Cu-AD-AA; and (G) Cu-AD-PA. Pore structure displayed by Connolly surface of (H) Cu-AD-FA; (I) Cu-AD-AA; and (J) Cu-AD-PA. Color scheme. White: Hydrogen; gray: carbon; blue: nitrogen; red: oxygen; green: copper.

Thermal and chemical stability

The thermal stability of these materials was investigated through TGA analysis and variable temperature PXRD tests [Supplementary Figures 5 and 6]. Variable temperature PXRD tests revealed that Cu-AD-FA could withstand temperatures up to 100 oC before its structure collapsed at 150 oC [Supplementary Figure 6A]. Conversely, Cu-AD-AA demonstrated good crystallization even at 200 oC, with slight broadening observed at 250 oC and a significant decrease in crystallinity at 300 oC, accompanied by weakened peak intensity [Supplementary Figure 6B]. Similarly, Cu-AD-PA showed comparable thermal stability to Cu-AD-AA, maintaining strong peak intensity without broadening up to 250 oC but experiencing decreased crystallinity beyond that temperature [Supplementary Figure 6C]. After soaking in different solvents for three days, PXRD tests proved that the three compounds have excellent chemical stability [Supplementary Figure 7]. The water stability test was conducted. After one day of soaking the three MOFs materials in water, the samples were reactivated for nitrogen adsorption measurements. The results show that the water stability of the three materials is not good enough, but their resistance to water is slightly different, among which Cu-AD-PA has the strongest resistance to water, followed by Cu-AD-AA and Cu-AD-FA [Supplementary Figure 8]. These differences can be attributed to the hydrophobicity changes of the terminal ligands.

Porosity of Cu-AD-FA, Cu-AD-AA and Cu-AD-PA

Prior to the 77 K nitrogen adsorption test, these three MOFs underwent pre-activation. Approximately

The resulting 77 K nitrogen adsorption isotherm is depicted in Figure 2A. Among them, Cu-AD-AA exhibits the highest adsorption capacity, with its actual pore volume closely aligning with theoretical values. Conversely, Cu-AD-FA falls short of reaching its theoretical pore volume due to partial skeleton collapse, whereas Cu-AD-PA successfully achieves its theoretical pore volume. Compared to previously reported works[49], the three materials synthesized via solvothermal synthesis in this study show significantly fewer defects and notable improvements in pore volume and Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) specific surface area [Table 1], indicating that these MOFs materials in this work are more suitable for gas adsorption and separation investigation. The pore size distributions of Cu-AD-FA, Cu-AD-AA and Cu-AD-PA calculated by the nonlocal density functional theory (NLDFT) model, which are basically consistent with the dimensions measured by the crystal structure [Figure 2B]. The pore volume and thermal stability of these three materials exhibit a remarkable trade-off effect. Specifically, Cu-AD-AA demonstrates optimal properties, displaying enhanced stability and a high BET specific surface area.

Figure 2. (A) N2 sorption isotherms for Cu-AD-FA, Cu-AD-AA and Cu-AD-PA at 77 K; (B) The pore size distributions of Cu-AD-FA, Cu-AD-AA and Cu-AD-PA calculated by NLDFT model. NLDFT: Non-local density functional theory.

BET surface area, Langmuir surface area, pore volume measured by experiment, theoretical pore volume and comparison of pore volume reported in the literature[49]

| MOFs | BET (m2/g) | Langmuir (m2/g) | Pore volume (cm3/g) | Theoretical pore volume (cm3/g) | Reference pore volume (cm3/g) |

| Cu-AD-FA | 650 | 672 | 0.24 | 0.35 | - |

| Cu-AD-AA | 712 | 754 | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.17 |

| Cu-AD-PA | 662 | 688 | 0.20 | 0.23 | 0.11 |

Gas adsorption behavior of Cu-AD-FA, Cu-AD-AA and Cu-AD-PA

To comprehensively elucidate the impact of pore microenvironment changes on gas adsorption properties, adsorption isotherms of CO2 and C1-C3 light hydrocarbon gas molecules were tested at 273 and 298 K, respectively [Supplementary Figures 10-13]. In order to more clearly describe the adsorption properties of these MOFs materials, the adsorption isotherms at 298 K and their adsorption enthalpies (Qst) were shown in Figure 3. The adsorption capacity of C3 and C2 molecules for the three MOFs is significantly higher than that of CH4 [Figure 3A-C]. This discrepancy stems from the greater polarizability and larger molecular size of C2 and C3, facilitating stronger interactions with the framework [Supplementary Table 3]. Notably, the variance in adsorption capacity is most pronounced at low pressures. Detailed specific adsorption values at 10 kPa and 101 kPa at 298 K can be found in Supplementary Table 4. Regarding C2 molecules, the presence of polar sites within the pores plays a crucial role in their binding ability. In terms of a horizontal comparison, C2H2 possesses the smallest pKa value and can form hydrogen bonds with numerous amino and nitrogen atoms within the pores, leading to higher adsorption capacity than C2H4 and C2H6. C2H4 and C2H6 exhibit similar sizes and polarities, consequently resulting in comparable adsorption capacities. From a longitudinal perspective, the channel environment undergoes minimal changes from Cu-AD-FA to

Figure 3. CO2, CH4, C2H2, C2H4, C2H6, C3H6 and C3H8 adsorption isotherms of (A) Cu-AD-FA; (B) Cu-AD-AA; (C) Cu-AD-PA at 298 K and 1 bar. Qst curves of (D) Cu-AD-FA; (E) Cu-AD-AA; (F) Cu-AD-PA.

To assess the interaction strength between the host framework and these light hydrocarbons and CO2, the adsorption enthalpies for the three MOFs were calculated. The Virial equation was employed to fit the adsorption curves at 273 K and 298 K, from which the Qst values were derived [Supplementary Figures 14-17]. As depicted in Figure 3D, the Qst values of Cu-AD-FA for various gases are as follows: CO2 (28.3 kJ/mol), CH4 (15.7 kJ/mol), C2H2 (24.8 kJ/mol), C2H4 (21.7 kJ/mol), C2H6 (21.3 kJ/mol), C3H6 (25.1 kJ/mol), and C3H8 (24.2 kJ/mol). In contrast, Cu-AD-AA exhibits significantly higher Qst for C3H6 (48.7 kJ/mol) and C3H8 (43.1 kJ/mol) compared to CH4 (16.4 kJ/mol). Additionally, the Qst of Cu-AD-AA for CO2, C2H2,

Gas separation behavior of Cu-AD-FA, Cu-AD-AA and Cu-AD-PA

As illustrated in Supplementary Figures 18-20, the adsorption data (CO2, CH4, C2H2, C2H4, C2H6, C3H6, and C3H8) obtained from experiments for Cu-AD-FA, Cu-AD-AA, and Cu-AD-PA were fitted using the dual-site Langmuir-Freundlich equation. The fitting parameters are within the error range and are listed in Supplementary Tables 5-7. The theoretical selectivity of Cu-AD-FA, Cu-AD-AA, and Cu-AD-PA for C2H2/CH4, C2H4/CH4, C2H6/CH4, and C3H8/CH4 was predicted by ideal adsorbed solution theory (IAST) calculations. The selectivity for C3H8/CH4 (0.5:0.5) was found to be 36, 746, and 31 for Cu-AD-FA, Cu-AD-AA, and Cu-AD-PA, respectively [Figure 4A]. For C2H6/CH4 (0.5:0.5), the selectivity was 29, 50, and 28, respectively [Figure 4B]. Similarly, for C2H2/CH4 (0.5:0.5), the selectivity was 53, 81, and 68 for Cu-AD-FA, Cu-AD-AA, and Cu-AD-PA, respectively, and for C2H4/CH4 (0.5:0.5), the selectivity was 34, 54, and 34 [Supplementary Figure 21]. Notably, Cu-AD-AA exhibits higher selectivity for C3H8/CH4 and

Figure 4. (A) Selectivity of equimolar mixtures of C3H8 over CH4 for Cu-AD-FA, Cu-AD-AA and Cu-AD-PA; (B) Selectivity of equimolar mixtures of C2H6 over CH4 for Cu-AD-FA, Cu-AD-AA and Cu-AD-PA; (C) Selectivity of equimolar mixtures of C3H6 over C2H4 for Cu-AD-FA, Cu-AD-AA and Cu-AD-PA; (D) Comparison of IAST selectivity of C3H6/C2H4 (0.5/0.5) with other reported MOFs. IAST: Ideal adsorbed solution theory; MOFs: metal–organic frameworks.

The selectivity for the separation of MTO product was also determined using IAST calculations [Figure 4C and Supplementary Figure 24]. Supplementary Figures 18 and 20 illustrate the adsorption capacities of C3H6 for Cu-AD-FA and Cu-AD-PA, which are initially higher than those of C2H4 at low pressures. However, the adsorption capacity of C2H4 surpasses that of C3H6 shortly thereafter. Consequently, these MOFs are unsuitable for effectively separating the C3H6/C2H4 mixture. In contrast, Cu-AD-AA exhibits a higher adsorption capacity for C3H6 compared to C2H4 in both low and high pressure regions [Supplementary Figure 19]. The IAST results presented in Figure 4C and Supplementary Figure 24 indicate that Cu-AD-AA demonstrates selectivity values of 10.9 (v/v = 0.1/0.9), 10.8 (v/v = 0.2/0.5), and 10.9 (v/v = 0.5/0.5) for different proportions of C3H6/C2H4. Conversely, the equimolar selectivity of Cu-AD-FA and Cu-AD-PA decreases to 1.1 and 1.9 at 101 kPa, indicating their inability to effectively separate C3H6 and C2H4. Notably, the C3H6/C2H4 selectivity of Cu-AD-AA exceeds that of numerous reported materials. As shown in Figure 4D, the selectivity of Cu-AD-AA ranks second, only surpassed by Zn2(oba)2(dmimpym) (15.6)[64], and is higher than those reported same type MOFs materials, such as CoV-(CF3)3bdc-tpt (10.1)[65], Y-pek-MOF-1 (9.0)[15], NEM-7-Cu (8.61)[66], Mn-dtzip (8.6)[67], spe-MOF (7.7)[16] and Zn-BPZ-SA (4.8)[36]. A more detailed comparison is listed in Supplementary Table 9.

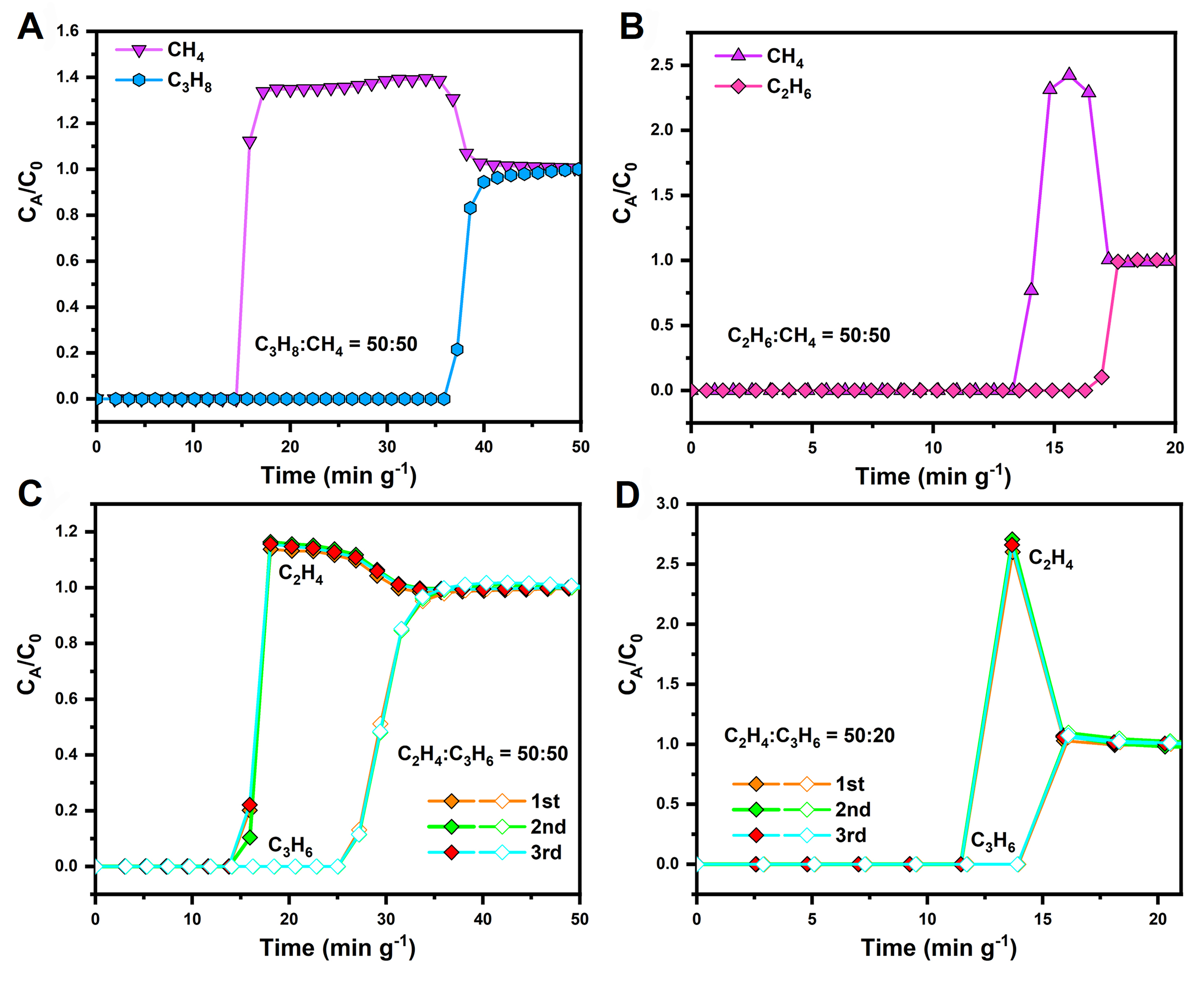

Among the three MOFs, Cu-AD-AA has the best adsorption capacity and the highest selectivity, achieving a balance between adsorption capacity and selectivity. To assess Cu-AD-AA practical separation capability, dynamic breakthrough experiments were conducted at 298 K and 1 bar. Figure 5A illustrates the breakthrough of a gas mixture with a C3H8/CH4 ratio of 50/50 (flow rate: 2 mL/min). Over time, CH4 rapidly elutes from the column while C3H8 remains retained. Calculations indicate that a single breakthrough experiment yields high-purity CH4 at 1.25 mmol/g. Similarly, Figure 5B demonstrates that after the passage of a C2H6/CH4 gas mixture (50/50, 2 mL/min), CH4 breaks through first, followed by C2H6 after a certain period. The calculated CH4 yield is 0.22 mmol/g. These results indicate that Cu-AD-AA possesses exceptional natural gas purification capabilities.

Figure 5. The breakthrough curves of the (A) C3H8/CH4 mixtures (v/v = 50/50 under a flow of 2 mL/min); (B) C2H6/CH4 mixtures

For MTO product separation, a mixture of C2H4:C3H6 was introduced into activated Cu-AD-AA samples packed in a column at flow rates of 2.0, 4.0, and 5.0 mL/min with ratios of 50:50 [Figure 5C], 50:20 [Figure 5D], and 90:10 [Supplementary Figure 25], respectively. The observations demonstrated that

CONCLUSIONS

In this study, three AD-based Bio-MOFs were successfully synthesized using a solvothermal method, employing monocarboxylic acids with varying sizes as coordinated terminal ligands. These MOFs exhibited distinct pore microenvironments arising from differences in terminal ligand sizes. Systematic investigation revealed a significant enhancement of thermal stability with larger terminal ligands. Furthermore, evaluation of their adsorption properties for light hydrocarbons revealed diverse capacities for adsorption and selective separation, attributable to their three-dimensional intercrossed channels and abundant active sites within. As a result, it demonstrated their aptitude for adsorbing C3 > C2 > C1 molecules, making them suitable for natural gas purification and MTO product separation. Qualitative analysis through IAST further confirmed the potential of these Bio-MOFs in CH4 purification and MTO product separation, with

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Provided financial support: Liu Y

Revised and finalized the manuscript: Liu Y, Zhang L

Designed the samples, performed experiments, and wrote the paper: Liu Y, Li W, Zhang L

Offered the experimental guidance and advice: Xue D

Assisted with data supplement: Wang Y, Wang D, Shi Z, Liu J

All authors contributed to the general discussion.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 22171100 and U23A20360) and the 111 Project (B17020).

Conflicts of interest

All authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2024.

Supplementary Materials

REFERENCES

1. Yang Y, Li L, Lin RB, et al. Ethylene/ethane separation in a stable hydrogen-bonded organic framework through a gating mechanism. Nat Chem 2021;13:933-9.

2. Jiang Y, Hu Y, Luan B, et al. Benchmark single-step ethylene purification from ternary mixtures by a customized fluorinated anion-embedded MOF. Nat Commun 2023;14:401.

3. Fan W, Ying Y, Peh SB, et al. Multivariate polycrystalline metal–organic framework membranes for CO2/CH4 separation. J Am Chem Soc 2021;143:17716-23.

4. Zhang Z, Deng Z, Evans HA, et al. Exclusive recognition of CO2 from hydrocarbons by aluminum formate with hydrogen-confined pore cavities. J Am Chem Soc 2023;145:11643-9.

5. Ryckebosch E, Drouillon M, Vervaeren H. Techniques for transformation of biogas to biomethane. Biomass Bioenerg 2011;35:1633-45.

6. Li L, Lin RB, Krishna R, et al. Ethane/ethylene separation in a metal–organic framework with iron-peroxo sites. Science 2018;362:443-6.

7. Liu Y, Chen Z, Liu G, et al. Conformation-controlled molecular sieving effects for membrane-based propylene/propane separation. Adv Mater 2019;31:e1807513.

8. Zhang Y, Xiao H, Zhou X, Wang X, Li Z. Selective adsorption performances of UiO-67 for separation of light hydrocarbons C1, C2, and C3. Ind Eng Chem Res 2017;56:8689-96.

9. Han XH, Gong K, Huang X, et al. Syntheses of covalent organic frameworks via a one-pot suzuki coupling and schiff’s base reaction for C2H4/C3H6 separation. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2022;61:e202202912.

10. Tian P, Wei Y, Ye M, Liu Z. Methanol to olefins (MTO): from fundamentals to commercialization. ACS Catal 2015;5:1922-38.

11. Chen Y, Yang Y, Wang Y, et al. Ultramicroporous hydrogen-bonded organic framework material with a thermoregulatory gating effect for record propylene separation. J Am Chem Soc 2022;144:17033-40.

12. Chen KJ, Madden DG, Mukherjee S, et al. Synergistic sorbent separation for one-step ethylene purification from a four-component mixture. Science 2019;366:241-6.

13. Liu Y, Liu J, Xiong H, et al. Negative electrostatic potentials in a Hofmann-type metal–organic framework for efficient acetylene separation. Nat Commun 2022;13:5515.

14. Peng YL, Wang T, Jin C, et al. Efficient propyne/propadiene separation by microporous crystalline physiadsorbents. Nat Commun 2021;12:5768.

15. Wei W, Guo X, Zhang Z, Zhang Y, Xue D. Topology-guided synthesis and construction of amide-functionalized rare-earth metal–organic frameworks. Inorg Chem Commun 2021;133:108896.

16. Fang H, Zheng B, Zhang ZH, Li HX, Xue DX, Bai J. Ligand-conformer-induced formation of zirconium-organic framework for methane storage and MTO product separation. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2021;60:16521-8.

17. Gao S, Morris CG, Lu Z, et al. Selective hysteretic sorption of light hydrocarbons in a flexible metal–organic framework material. Chem Mater 2016;28:2331-40.

18. Hiraide S, Sakanaka Y, Kajiro H, Kawaguchi S, Miyahara MT, Tanaka H. High-throughput gas separation by flexible metal–organic frameworks with fast gating and thermal management capabilities. Nat Commun 2020;11:3867.

19. Fan W, Zhang X, Kang Z, Liu X, Sun D. Isoreticular chemistry within metal–organic frameworks for gas storage and separation. Coord Chem Rev 2021;443:213968.

20. Li J, Bhatt PM, Li J, Eddaoudi M, Liu Y. Recent progress on microfine design of metal–organic frameworks: structure regulation and gas sorption and separation. Adv Mater 2020;32:e2002563.

21. Hu P, Hu J, Liu H, et al. Quasi-orthogonal configuration of propylene within a scalable metal–organic framework enables its purification from quinary propane dehydrogenation byproducts. ACS Cent Sci 2022;8:1159-68.

22. Zeng H, Xie M, Wang T, et al. Orthogonal-array dynamic molecular sieving of propylene/propane mixtures. Nature 2021;595:542-8.

23. Long JR, Yaghi OM. The pervasive chemistry of metal–organic frameworks. Chem Soc Rev 2009;38:1213-4.

25. Zheng F, Chen R, Ding Z, et al. Interlayer symmetry control in flexible-robust layered metal–organic frameworks for highly efficient C2H2/CO2 separation. J Am Chem Soc 2023;145:19903-11.

26. Gulati S, Vijayan S, Mansi, et al. Recent advances in the application of metal–organic frameworks (MOFs)-based nanocatalysts for direct conversion of carbon dioxide (CO2) to value-added chemicals. Coord Chem Rev 2023;474:214853.

27. Li L, Jung HS, Lee JW, Kang YT. Review on applications of metal–organic frameworks for CO2 capture and the performance enhancement mechanisms. Renew Sust Energy Rev 2022;162:112441.

28. Yang S, Hu T. Reverse-selective metal–organic framework materials for the efficient separation and purification of light hydrocarbons. Coord Chem Rev 2022;468:214628.

29. Xie Y, Shi Y, Cedeño Morales EM, et al. Optimal binding affinity for sieving separation of propylene from propane in an oxyfluoride anion-based metal–organic framework. J Am Chem Soc 2023;145:2386-94.

30. Deneff JI, Rohwer LES, Butler KS, et al. Orthogonal luminescence lifetime encoding by intermetallic energy transfer in heterometallic rare-earth MOFs. Nat Commun 2023;14:981.

31. Liu Q, Wu B, Li M, Huang Y, Li L. Heterostructures made of upconversion nanoparticles and metal–organic frameworks for biomedical applications. Adv Sci 2022;9:e2103911.

32. Hashjin M, Zarshad S, Motejadded Emrooz HB, Sadeghzadeh S. Enhanced atmospheric water harvesting efficiency through green-synthesized MOF-801: a comparative study with solvothermal synthesis. Sci Rep 2023;13:16983.

33. Shi L, Li N, Wang D, Fan M, Zhang S, Gong Z. Environmental pollution analysis based on the luminescent metal organic frameworks: a review. TrAC Trend Anal Chem 2021;134:116131.

35. Datta SJ, Mayoral A, Murthy Srivatsa Bettahalli N, et al. Rational design of mixed-matrix metal–organic framework membranes for molecular separations. Science 2022;376:1080-7.

36. Wang G, Krishna R, Li Y, et al. Rational construction of ultrahigh thermal stable MOF for efficient separation of MTO products and natural gas. ACS Mater Lett 2023;5:1091-9.

37. Dong Q, Huang Y, Hyeon-deuk K, et al. Shape- and size-dependent kinetic ethylene sieving from a ternary mixture by a trap-and-flow channel crystal. Adv Funct Mater 2022;32:2203745.

38. Yaghi OM. Reticular chemistry-construction, properties, and precision reactions of frameworks. J Am Chem Soc 2016;138:15507-9.

39. Ke T, Wang Q, Shen J, et al. Molecular sieving of C2-C3 alkene from alkyne with tuned threshold pressure in robust layered metal–organic frameworks. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2020;59:12725-30.

40. Eddaoudi M, Kim J, Rosi N, et al. Systematic design of pore size and functionality in isoreticular MOFs and their application in methane storage. Science 2002;295:469-72.

41. Pei J, Wang J, Shao K, et al. Engineering microporous ethane-trapping metal–organic frameworks for boosting ethane/ethylene separation. J Mater Chem A 2020;8:3613-20.

42. Meng SS, Xu M, Guan H, et al. Anisotropic flexibility and rigidification in a TPE-based Zr-MOFs with scu topology. Nat Commun 2023;14:5347.

43. Lyu H, Chen OI, Hanikel N, et al. Carbon dioxide capture chemistry of amino acid functionalized metal–organic frameworks in humid flue gas. J Am Chem Soc 2022;144:2387-96.

44. Zulys A, Yulia F, Muhadzib N, Nasruddin. Biological metal–organic frameworks (Bio-MOFs) for CO2 capture. Ind Eng Chem Res 2021;60:37-51.

45. Binaeian E, Nabipour H, Ahmadi S, Rohani S. The green synthesis and applications of biological metal–organic frameworks for targeted drug delivery and tumor treatments. J Mater Chem B 2023;11:11426-59.

46. Si Y, Luo H, Zhang P, et al. CD-MOFs: from preparation to drug delivery and therapeutic application. Carbohydr Polym 2024;323:121424.

47. Wang L, Lv J, Ye Q, Luo Y, Wang G, Xie L. Nanoporous Cu(II)-adenine-based metal–organic frameworks for selective adsorption of C2H2 from C2H4 and CO2. ACS Appl Nano Mater 2023;6:22095-103.

48. Li T, Chen D, Sullivan JE, Kozlowski MT, Johnson JK, Rosi NL. Systematic modulation and enhancement of CO2:N2 selectivity and water stability in an isoreticular series of bio-MOF-11 analogues. Chem Sci 2013;4:1746-55.

49. Pérez-Yáñez S, Beobide G, Castillo O, et al. Open-framework copper adeninate compounds with three-dimensional microchannels tailored by aliphatic monocarboxylic acids. Inorg Chem 2011;50:5330-2.

50. Pérez-yáñez S, Beobide G, Castillo O, et al. Gas adsorption properties and selectivity in CuII/adeninato/carboxylato metal–biomolecule frameworks. Eur J Inorg Chem 2012;2012:5921-33.

51. Li H, Bonduris H, Zhang X, et al. A microporous metal–organic framework with basic sites for efficient C2H2/CO2 separation. J Solid State Chem 2020;284:121209.

52. Song C, Zheng F, Liu Y, et al. Spatial distribution of nitrogen binding sites in metal–organic frameworks for selective ethane adsorption and one-step ethylene purification. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2023;62:e202313855.

53. Chen OIF, Liu CH, Wang K, et al. Water-enhanced direct air capture of carbon dioxide in metal–organic frameworks. J Am Chem Soc 2024;146:2835-44.

54. Liu X, Kirlikovali KO, Chen Z, et al. Small molecules, big effects: tuning adsorption and catalytic properties of metal–organic frameworks. Chem Mater 2021;33:1444-54.

55. Xie Y, Shi Y, Cui H, Lin R, Chen B. Efficient separation of propylene from propane in an ultramicroporous cyanide-based compound with open metal sites. Small Struct 2022;3:2100125.

56. Yang SQ, Sun FZ, Krishna R, et al. Propane-trapping ultramicroporous metal–organic framework in the low-pressure area toward the purification of propylene. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2021;13:35990-6.

57. Peng Y, Wang T, Jin C, et al. A robust heterometallic ultramicroporous MOF with ultrahigh selectivity for propyne/propylene separation. J Mater Chem A 2021;9:2850-6.

58. Gao J, Cai Y, Qian X, et al. A microporous hydrogen-bonded organic framework for the efficient capture and purification of propylene. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2021;60:20400-6.

59. Zhou J, Ke T, Steinke F, et al. Tunable confined aliphatic pore environment in robust metal–organic frameworks for efficient separation of gases with a similar structure. J Am Chem Soc 2022;144:14322-9.

60. Shi R, Lv D, Chen Y, et al. Highly selective adsorption separation of light hydrocarbons with a porphyrinic zirconium metal–organic framework PCN-224. Sep Purif Technol 2018;207:262-8.

61. Huang Y, Lin Z, Fu H, et al. Porous anionic indium-organic framework with enhanced gas and vapor adsorption and separation ability. ChemSusChem 2014;7:2647-53.

62. Zhang Y, Yang L, Wang L, Duttwyler S, Xing H. A microporous metal–organic framework supramolecularly assembled from a CuII dodecaborate cluster complex for selective gas separation. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2019;58:8145-50.

63. Zhang Y, Yang L, Wang L, Cui X, Xing H. Pillar iodination in functional boron cage hybrid supramolecular frameworks for high performance separation of light hydrocarbons. J Mater Chem A 2019;7:27560-6.

64. Li YZ, Wang GD, Krishna R, et al. A separation MOF with O/N active sites in nonpolar pore for one-step C2H4 purification from

65. Xiao Y, Hong AN, Chen Y, et al. Developing water-stable pore-partitioned metal–organic frameworks with multi-level symmetry for high-performance sorption applications. Small 2023;19:2205119.

66. Liu X, Hao C, Li J, et al. An anionic metal–organic framework: metathesis of zinc(II) with copper(II) for efficient C3/C2 hydrocarbon and organic dye separation. Inorg Chem Front 2018;5:2898-905.

Cite This Article

Export citation file: BibTeX | RIS

OAE Style

Li W, Wang D, Wang Y, Shi Z, Liu J, Zhang L, Xue D, Liu Y. Biological metal–organic frameworks for natural gas purification and MTO product separation. Chem Synth 2024;4:22. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/cs.2023.69

AMA Style

Li W, Wang D, Wang Y, Shi Z, Liu J, Zhang L, Xue D, Liu Y. Biological metal–organic frameworks for natural gas purification and MTO product separation. Chemical Synthesis. 2024; 4(2): 22. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/cs.2023.69

Chicago/Turabian Style

Li, Wen, Dan Wang, Yi Wang, Zhaohui Shi, Junxue Liu, Lirong Zhang, Dongxu Xue, Yunling Liu. 2024. "Biological metal–organic frameworks for natural gas purification and MTO product separation" Chemical Synthesis. 4, no.2: 22. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/cs.2023.69

ACS Style

Li, W.; Wang D.; Wang Y.; Shi Z.; Liu J.; Zhang L.; Xue D.; Liu Y. Biological metal–organic frameworks for natural gas purification and MTO product separation. Chem. Synth. 2024, 4, 22. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/cs.2023.69

About This Article

Special Issue

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Cite This Article 0 clicks

Cite This Article 0 clicks

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at support@oaepublish.com.